With the formal signing of the armistice agreement on July 27, 1953, new and surprising challenges emerged despite its relatively smooth direct implementation in the field of silencing guns. After just a few days, the agreed-upon deployed personnel by the Armistice Commission for implementation (max. 1,000 persons per side) would be replaced by military police instead of civilian and lightly armed police personnel, as had been planned. In practice, this meant armed personnel of regular infantry formations wearing the black armband with MP on it (still in use today) was deployed and continues to this day. The formations on the northern side originally wore corresponding red armbands but they no longer do.

The parties to conflict established the Military Armistice Commission (MAC) to manage the implementation and compliance of the terms of the Armistice, to investigate alleged violations, to serve as an intermediary between the commanders of the opposing sides, and to settle through negotiation any violations of the Armistice Agreement. The MAC is a combined organization consisting of ten senior military officers: five through UNC Commander appointment and five appointed by the commanders of the KPA and CPV. Both sides also formed cease-fire commissions. In the south the United Nations Military Armistice Commission, UNCMAC, still today is operationally and multi-nationally composed and has been led by a Korean **general since 1992.

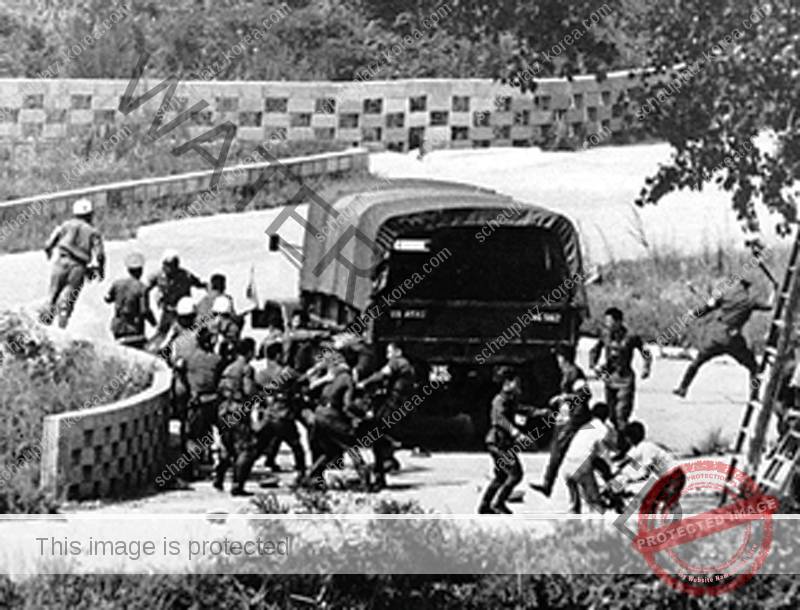

Negotiations have been very tough from the start. Requests for investigations of violations rarely are dealt with, let alone implemented. For the total duration of the MAC’s activities, until the North unilaterally withdrew in 1991, very few concrete decisions were made, and even less implemented. Major changes regarding the framework usually resulted from serious incidents such as the Axe Murder Incident in August 1976 in the Joint Security Area JSA or in countermeasures in response to obvious violations by the other side (e.g., the establishment of fortified posts within the DMZ starting in the mid-1970s). The MAC was not in a position to sanction or even reverse these violations.

This explains why the DMZ has become the “most highly militarized demilitarized zone” on the planet in its 70 years of existence. Meanwhile, massively improved capabilities have been built up (only the upper limit of 35,000 stationed persons of foreign contingents stipulated in the agreement has never been exceeded or violated except during short-term exercise activities), thus considerably increasing the risk of miscalculations at the confrontation line. At present, the risk of a major incident can certainly be compared with the worrying phase of 2017.

Against this background, the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission, NNSC, faced considerable challenges. Even the history of its creation was marked by difficulties. The idea of a neutral supervisory commission was surprisingly introduced by the North into the armistice negotiations in the fall of 1951 and accepted with some skepticism in Washington, which was confirmed by the nomination proposal of the Soviet Union on the part of the North. In December 1951, the Federal Council responded positively in principle to a request from the U.S. State Department. The head of the Political Department, Federal Councilor Max Petitpierre, saw this as an opportunity to put the term “neutrality” in a rather positive light even if the U.S. had repeatedly hampered economic negotiations up to that point.

During the arduous armistice negotiations, repeatedly interrupted until the death of Josef Stalin in March 1953, numerous meetings and negotiations took place in Washington and Switzerland on the scope, composition, ranks, and competencies of the delegations to be created. From the Swiss point of view, the concern about the “neutrality compatibility” of the commitment was always in the foreground. The rather surprising “breakthrough” in Panmunjom also put the Federal Council and EMD, in charge of the implementation, under time pressure. It was not until July 13, 1953, the Federal Council formally commissioned the EMD.

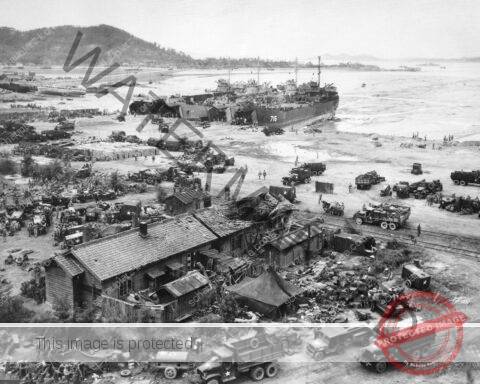

It is remarkable that a contingent of 146 Army personnel, 96 of them for the NNSC and 50 from the Repatriation Commission (NNRC), could be recruited and sent to Korea on time. The bulk was personally discharged at the end of July 1953 by the head of the EMD, Federal Councilor Karl Kobelt. The equipment is rudimentary and not adequate for the climatic conditions in Korea; the journey from Ramstein with American transport planes is adventurous and long at 25,000 km, 65 flying hours with 8 stopovers.

The beginning years are characterized by disappointing political expectations, a lot of operational learning but also frustration, especially on the delegation heads of Sweden and Switzerland.

Urs Gerber

On August 1, 1953, 4 days after the signing of the armistice, the first meeting of the NNSC takes place in Panmunjom. From the beginning, it is clear the idea made perfect sense in theory, yet in the geopolitical and ideological framework of the Cold War and Korea, despite the label neutral, it is immediately confronted with sometimes insurmountable difficulties. The delegations of Poland and Czechoslovakia are regarded as allies by the North and were. The Swedes and Swiss try as best they can to implement the mandate but are soon confronted with American dissatisfaction as well as South Korea’s rejection of the commission due to their justified accusations of espionage from Polish and Czechoslovak members of the mixed inspection teams.

Until the unilateral cessation of NNSC inspections at each of the five “points of entry” for personnel, weapons, and material in June 1956 by the UNC, they never once succeeded in reaching a common position for the attention of the Armistice Commission. The Commission does not at all fulfill the required expectation neither of the UNC or the Armistice Agreement in the most important part of the mandate. The beginning years are characterized by disappointing political expectations, and a lot of operational learning but also frustration, especially for the delegation heads of Sweden and Switzerland.

Within six months discreet diplomatic demands for mission termination were signaled and an official letter from the two heads of delegation in May 1954 requested termination. The continuation of the NNSC’s mission and the viability of the entire treaty framework was on a knife’s edge! This was further accentuated after the subsequent politically negotiated solution demanded by the treaty failed in Geneva in July 1954: The Indochina question pushed the solution to the Korean question into the background!

The concluding episode on the very difficult start of the NNSC in Korea will follow soon!

In our series of five articles on the Korean War, our expert and historian Urs Gerber write about the Korean War. He is Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Center for the Asia Pacific Strategy (CAPS), Washington. The Center for Asia Pacific Strategy is led by a talented team of directors from diverse backgrounds, all with extensive knowledge of the Asia-Pacific region first-hand and direct contacts. Major General (Ret.) Urs Gerber is the president of the Foundation Council of the Swiss Armed Forces’ Historic Material Foundation an institution responsible for collecting, maintaining, and developing the “hardware legacy” of the Swiss Armed Forces. He is co-chairing the Annual Senior Officers Seminar (ASOS) on leadership and crisis management at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP). From February 2012 until August 2017 Maj Gen Gerber has been the Swiss Member and Head of the Swiss Delegation to the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission, Panmunjeom, Republic of Korea, from where he retired at the end of August 2017.