After the Chinese offensive directed at Seoul was repulsed toward the end of April 1951, offensive forces on both sides waned after an energetic first year of the war. Moreover, approval ratings reached ever lower levels in the U.S. for the already unpopular Korean War. Thus it was not surprising the real “leading powers” from both sides, the United States and the Soviet Union, were exploring the possibilities for cease-fire negotiations through diplomatic channels. On June 30, 1951, in response to a request from the commander of the United Nations Command (UNC), General Matthew Ridgway, Joseph Stalin personally gave the green light in a letter to Mao Zedong:

CIPHERED TELEGRAM No. 3917

BEIJING – TO KRASOVSKY

for Comrade MAO ZEDONG

Your telegrams about an armistice have been received.

In our opinion it is necessary immediately to answer Ridgway over the radio with agreement to meet with his representatives for negotiations about an armistice. This communication must be signed by the Command of the Korean People’s Army and the command of the Chinese volunteer units, consequently by Comrade KIM IL SUNG and Comrade PENG DEHUAI. If there is no signature of the commander of the Chinese volunteer units, then the Americans will not attach any significance to only one Korean signature. It is necessary decisively to refuse the Danish hospital ship in the area of Wonsan as a place of meeting. It is necessary to demand that the meeting take place at the 38th parallel in the region of Gaeseong [Kaesong]. Keep in mind that at the present time you are the bosses of the affair of an armistice and the Americans will be forced to make concessions on the question of a place for the meeting.

Send to Ridgway today an answer roughly like this:

“To the commander of UN troops General RIDGWAY. Your statement of 28 June regarding an armistice has been received. We are authorized to declare to you that we agree to a meeting with your representatives for negotiations about a cessation of military actions and the establishment of an armistice. We propose as a meeting place the 38th parallel in the area of the city of Gaesong. If you agree, our representatives will be prepared to meet with your representatives July 10-15.”

Commander in Chief of the Korean People’s Army

KIM IL SUNG

Commander in Chief of the Chinese Volunteer Units

PENG DEHUAI

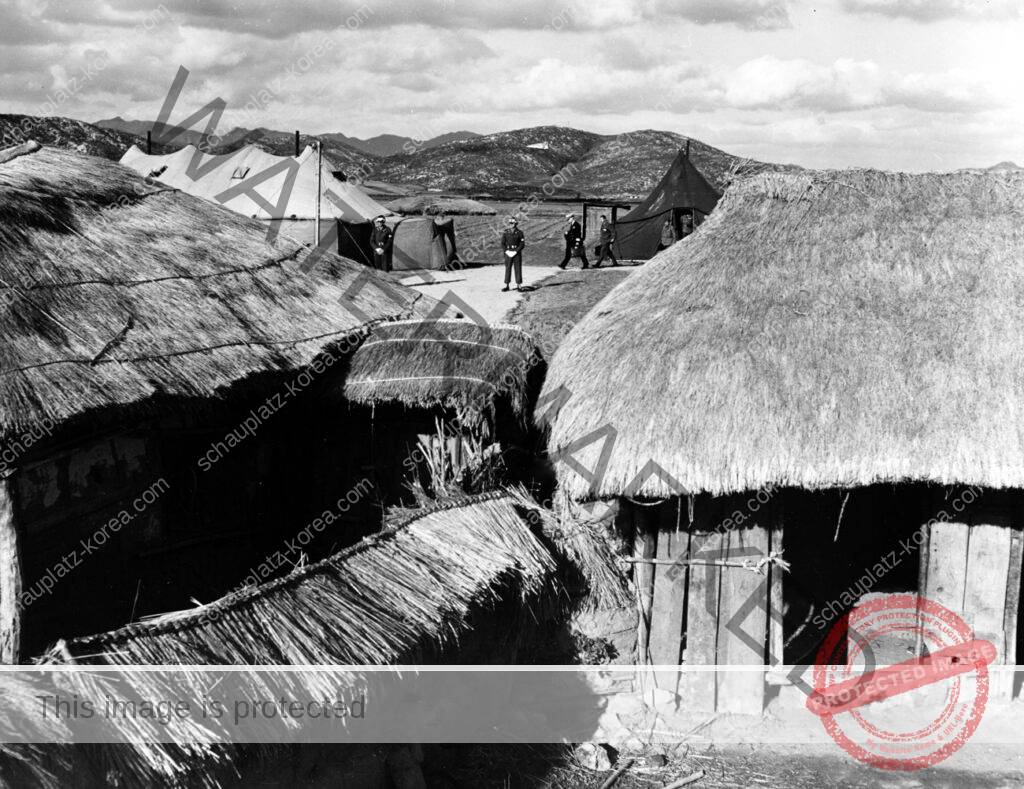

This began the process in the ancient Korean capitol of Kaesong which, in view of the war fatigue of the parties, should have led quickly to a result. Instead, the “merry-go-round talkathon” (called this by the American negotiator) took nearly 200 sessions with 400 hours over two years and 17 days. In late October 1951 the communists agreed to move the truce negotiations to a more secure area, a village named Panmunjom.

All the while fighting continued along the confrontation line in a war of position comparable to World War I. From mid-1951 onward, this line corresponded, with few exceptions, to today’s demarcation line. Minimal terrain was gained despite the many soldiers lost. Battles for strategically important heights turned out to be particularly costly. Despite complete air superiority, the Souths’ efforts were particularly futile to conquer the Diamond Mountains (Kumgang-San) in the east of the peninsula. The U.S. Air Force air superiority was often intercepted by sorties of Soviet pilots in Chinese or North Korean uniforms with respective aircraft markings. This resulted in direct air combat between “Soviet” MiG-15s and U.S. fighter planes. For a long time this was kept secret for geostrategic reasons; both sides fearing the danger of escalation to the Cold War.

Negotiations at Panmunjom were stalled for a long time as no agreement could be reached on the demarcation line. Additional points with no agreement included the North insisting the complete repatriation of all prisoners of war, whilst the South insisted voluntary repatriation. With nearly 20,000 of the 90,000 prisoners of war interned in the South not wanting to return back to North Korea or China, it was complicated, and not until the spring of 1953 did new momentum restart the deadlocked armistice negotiations.

Negotiations resumed at Panmunjom on April 27, 1953, thanks to the first mutual exchange of POWs (Operation Little Switch) and, in contrast to earlier phases, moved forward rapidly. With Dwight D. Eisenhower moving into the White House on an election promise to escalate the war in Korea, and Josef Stalin’s unexpected death in early March, North Korea, and China had to accept significant portions of the UNC’s demands including an exchange of voluntary POWs and the creation of a neutral monitoring commission to finally settle the POW issue. This development contradicted the ideas of South Korean President Syngman Rhee to a considerable extent. He was determined to fight until the successful (re)unification of the Korean peninsula and saw, not unreasonably, that a cease-fire would probably put an end to this project in the long run.

South Korea neither approved nor agreed to the armistice; they merely “did not oppose” it. This attitude toward the armistice agreement is still prevalent among parts of the Korean elite today.

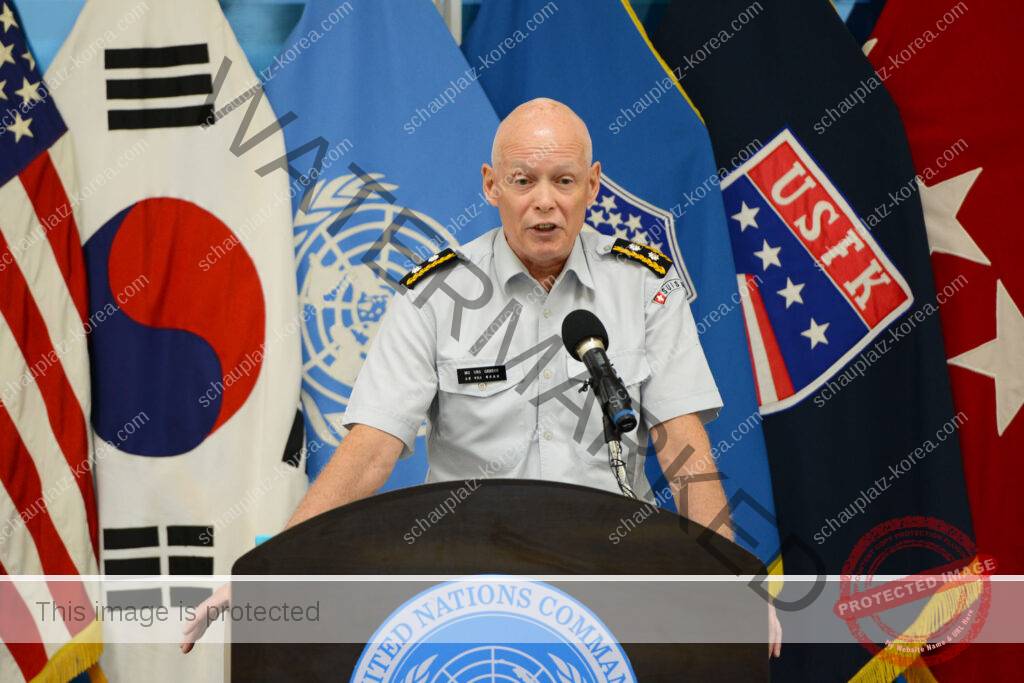

Urs Gerber

Rhee went so far in his obstructionism as to threaten South Korea’s withdrawal from the United Nations Command shortly before the conclusion of the cease-fire negotiations. He demanded the United States conclude a defense pact in the event of an armistice and begin negotiations on a peace order within 90 days or South Korea would continue the war unilaterally until reunification. Eisenhower relented but could not persuade Rhee to actively participate in signing the agreement. South Korea neither approved nor agreed to the armistice; they merely “did not oppose” it. This attitude toward the armistice agreement is still prevalent among parts of the Korean elite today.

Exactly three months after the resumption of talks, the Armistice Agreement was signed on July 27, 1953, a procedure that reflects the enormous mistrust between the two sides that continues more or less unabated to this day. To keep the supreme commanders of the two sides from having to meet, the signing ceremony took place simultaneously. In Kaesong with Kim Il Sung and Peng Dehuai signing, and in Munsan with Mark Clark the sole signatory for the UNC. Subsequently, the two negotiators signed in Panmunjom in the specially built “Peace Pagoda” without shaking hands and without exchanging a single word.

After the scheduled 72 hours, all formations on both sides had retreated behind their respective demarcation lines, but not without laying mines along the retreat. Their aim was to prevent any advance by the other side. Still today after almost 70 years large parts of the DMZ have never been entered for that reason. In the subsequent exchange of prisoners of war under Operation Big Switch, voluntary returnees were first exchanged under the supervision of the Neutral Repatriation Commission (NNRC). The exchange took place over the “Bridge of No Return,” named for the procedure that whoever crosses the bridge cannot turn back. Many prisoners particularly loyal to the regime demonstratively divested themselves of all clothing before crossing the bridge to the north to express their contempt for the South…

The last segment on this topic will follow soon featuring the armistice and its consequences together with the emergence of the Neutral Surveillance Commission (NNSC)!

In our series of five articles on the Korean War, our expert and historian Urs Gerber write about the Korean War. He is Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Center for the Asia Pacific Strategy (CAPS), Washington. The Center for Asia Pacific Strategy is led by a talented team of directors from diverse backgrounds, all with extensive knowledge of the Asia-Pacific region first-hand and direct contacts. Major General (Ret.) Urs Gerber is the president of the Foundation Council of the Swiss Armed Forces’ Historic Material Foundation an institution responsible for collecting, maintaining, and developing the “hardware legacy” of the Swiss Armed Forces. He is co-chairing the Annual Senior Officers Seminar (ASOS) on leadership and crisis management at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP). From February 2012 until August 2017 Maj Gen Gerber has been the Swiss Member and Head of the Swiss Delegation to the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission, Panmunjeom, Republic of Korea, from where he retired at the end of August 2017.